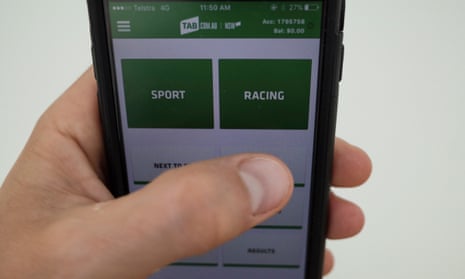

People on the brink of bankruptcy are spending considerably more on gambling, a phenomenon the Salvation Army has linked to the proliferation of online betting companies.

The Salvation Army on Tuesday released new data gleaned from its support service MoneyCare, which provides in-depth counselling to about 7,300 people in financial crisis each year.

The data shows people who sought help and disclosed gambling expenditure in 2016-17 were spending 8.38% of their income on betting, a 363.4% increase from 10 years earlier.

The head of the Moneycare service, Tony Devlin, said the increase appeared to be linked to the rise of online sports betting agencies and associated marketing.

Devlin said the advertising of many online agencies appeared targeted at lower socio-economic groups.

“It’s just easier and easier to do it all the time,” Devlin said. “The latest lot of ads I’ve seen encourage people when they’re having lunch, or in the elevator, just to get online and bet. So that’s having an effect, it’s a big increase in our client base.

“The online operators and others are really getting into that low-income market.”

The Salvation Army also found vulnerable Australians were finding themselves in far deeper debt than others.

Their clients were on average owing $2.55 of debt for every dollar they earned, a debt-to-income ratio of 255%, compared to the community average of 190%.

Debts were most commonly incurred through credit cards, personal loans, electricity bills, car loans, welfare, mortgages, phones and fines.

Devlin said many people seeking the Salvation Army’s help had incurred debt during a time of personal crisis, but then found themselves unable to make repayments.

That’s precisely what happened to Warren Downs, 56, of Goulburn, who worked for decades in mining and construction in Australia and abroad.

In 2013 after returning from work in Africa, Downs began experiencing vitreous haemorrhages in his eyes. His eye problems left him near-blind for months and unable to work.

Downs, struggling to meet his medical costs, took out a $13,000 personal loan from Commonwealth Bank, despite not having a job.

The loan was crippling. He was forced to claim social security for the first time in his life, but $500 of the $640 a fortnight went straight to rent.

“Then you’ve got to pay power and gas, that’s another $50,” Downs said. “It leaves me about $80 a fortnight to live, and still does, in fact. Nothing’s changed.

“I’m just surviving really, and that’s where I’m at.”

Downs sought help through the Moneycare service, and he said the loan was eventually wiped.

He still experiences haemorrhaging and is unable to return to his old work.

Downs now relies on charities and a budget grocery service to get by. The temperatures plummet in Goulburn in the winter, but Downs can’t afford heating.

“As long as they don’t put the rent up here, I’m alright. I feel lucky just to have that roof over my head,” he said.

“I’m a payment away from being homeless really, and that’s how homelessness happens. You get a domino effect of things happening – you’re going along smoothly and something happens, then you’re homeless.”

The Salvation Army data also shows a 140% increase in casual and part-time workers seeking financial help from the Salvation Army, a 93.3% increase in carers, and a 71.8% increase in pensioners.

“When you have that much debt, and you don’t have the ability to repay the debt … it really affects your health and wellbeing in a large way. There’s increases to stress, anxiety, depression,” Devlin said.

“It affects relationships, it affects sleep, physical and mental health, and of course it affects you financially in a very severe way.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion