Editor’s Note: The Beltrami County Historical Society is partnering with the Pioneer on a series of monthly articles highlighting the history of the area, with 2025's stories primarily focusing on women.

Bemidji and the surrounding towns were home to many madams and disorderly houses in the late 1800s to early 1900s. Here, we will explore a few of the well-known madams and their backstories.

Ethyl Blake: A prominent figure in early Bemidji

Ethyl Blake arrived in Bemidji as an 18-year-old actress with her 42-year-old husband, Charles C. Blake, a theater manager. Described as petite with blue eyes and Scandinavian coloring, she quickly established herself as an independent businesswoman in the growing lumber town.

Initially associated with a vaudeville theater on Second Street, Ethyl soon set her sights higher. In early 1900, she established the Delmonico Restaurant at 100 Minnesota Avenue, which the Bemidji Pioneer noted had "a side-door entrance, thus not necessitating those who wish to dine with a lady, to pass through the sample room in connection." The restaurant gained enough prominence to cater for the opening of the McElroy Hotel in March 1900.

By 1904, Ethyl began acquiring significant property holdings in Bemidji. Records show she purchased lots 13 and 14 in Block 21 from William Fournier for $2,000 in April 1904. These properties were located in the area known as "Depravity Hill," Bemidji's notorious red-light district. Insurance maps delicately referred to establishments in this area as "female boarding houses," though they functioned as saloons with additional services offered upstairs.

Ethyl's marriage to Charles Blake deteriorated during this period. In August 1904, authorities arrested Charles after Ethyl claimed he had beaten her and threatened her with a revolver. She was granted an absolute divorce in October of that same year.

Ethyl faced opposition to her businesses, sometimes violent in nature. In August 1904, the Northern Hotel, which she owned, was set on fire by "unknown incendiaries." In February 1907, another Blake building was damaged by fire. Ethyl took the arson attempts seriously, offering a substantial $1,000 reward for information about who instigated the February fire, specifically stating she wanted to ascertain who was behind the action and didn’t care who had actually set it. She wanted only "to punish the persons really to blame!"

Ethyl started moving her business operations to South Bemidji, purchasing multiple properties beginning in 1905. She bought lots along Clausen Avenue from various owners, establishing a presence near the main railway lines. This location proved controversial, as residents complained about the visibility of her establishment from passing trains.

Throughout her career in Bemidji, Ethyl maintained influential relationships. She was known to be "a special friend" of attorney H.J. Loud. During a 1909 grand jury hearing, testimony revealed this connection, noting that Loud appeared "on the public streets in the company of said prostitute" despite her known profession.

ADVERTISEMENT

Despite multiple attempts to close or destroy her businesses through legal means and arson, Ethyl persisted and expanded her property holdings throughout Bemidji, demonstrating remarkable resilience and business acumen in an era with limited opportunities for women.

Jennie McElroy: Rise and fall

Jennie McElroy made her mark in 1899 by constructing an impressive two-story building for her Royal Palace Saloon on Second Street. The grand opening in March 1900 was quite the affair — 300 handsome invitations were sent out with catering provided by Blake & Hicks of the Delmonico restaurant. The establishment was lauded as "the finest saloon in town" with top-of-the-line fixtures.

Her success proved short-lived. By September 1900, she was forced to relocate to "the Hill," Bemidji's red-light district. Within two years, she faced bankruptcy, owing various debts, including $148.61 in taxes. Though her building survived the 1904 fire that destroyed many establishments in the district, Jennie’s business did not. She moved to Minneapolis and the property was later purchased by Ed Rose, a name frequently connected with the industry.

Dutch Mary: The theatrical freelancer

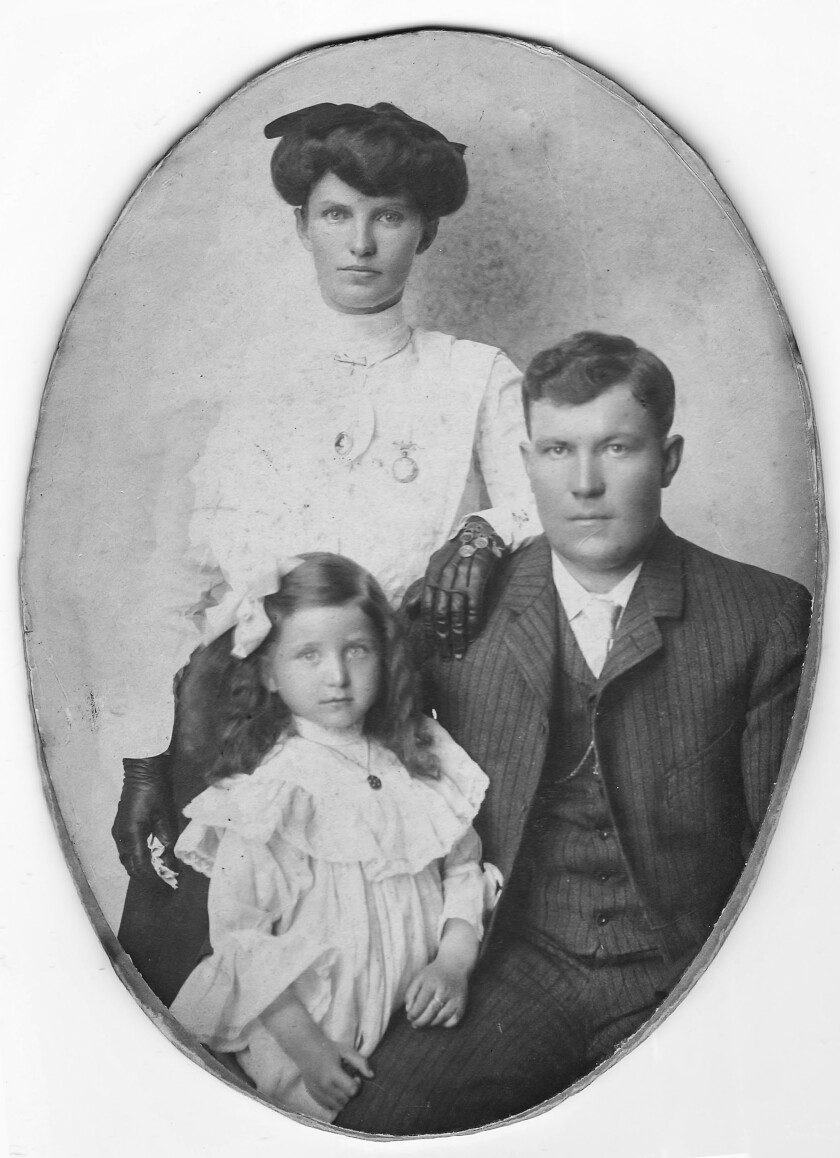

"Dutch Mary" Thompson defied easy categorization in Bemidji's vice world. Despite her nickname, she was actually Finnish, born as Mary Rynning in North Dakota. Her early life in Bemidji presented a veneer of respectability — photographs show her as a proper mother and wife with husband, Harry Thompson, and the girls. However, according to her grandson, she attempted to shield her four daughters by placing them with other families.

Unlike established madams who ran formal establishments, Dutch Mary carved out a unique niche. She operated the OK Restaurant at 120 Beltrami Avenue — a legitimate business that frequently violated Prohibition laws. She earned her nickname not from any Dutch heritage but from her association with a gambler known as "Dutch Slough."

Characterized by J.C. Ryan as one of the Lumberjack Queens, she was usually in trouble with the authorities for liquor violations rather than prostitution. Mary became famous for turning her regular arrests into street theater. On fine spring days, when police would escort her to pay fines, she would begin drinking early.

Lumberjacks would line the streets to watch her theatrical procession to City Hall, where she would wave, sing and provide a final flourish of lifted skirts before entering. Curiously, jail records show she never actually spent time in jail despite her reputation.

ADVERTISEMENT

As the business waned and regulations became tougher, Mary moved to Craigville in Koochiching County. It was frequented by as many as 5,000 lumberjacks seasonally. The women set up shop in tarpaper shacks row by row. Her story ended tragically in 1936 when she perished in a fire in one of the shacks near the International Lumber Company's operation at Craigville.

Bemidji's system of regulated vice

By 1901, Bemidji had evolved into a bustling frontier town with 42 saloons — including an impressive 11 on a single block. What distinguished Bemidji was not just the presence of these establishments but the careful social hierarchy that governed them.

"The Hill," a plateau along Irvine Avenue north of the Great Northern tracks, became the city's sanctioned red-light district. Insurance maps diplomatically labeled these as "female boarding houses." These establishments operated under unwritten but well-understood rules:

- Women were required to maintain genteel appearances

- They dressed well and rode in fine carriages

- A 5 p.m. curfew was strictly observed

- Street solicitation was forbidden

This created a façade of respectability that suited both operators and city officials. The contrast between "legitimate" and "illegitimate" operators was stark. While established madams like Ethyl Blake received favorable newspaper coverage and were treated as respected business owners, freelance operators faced regular arrest. This two-tiered system became particularly evident in the treatment of women operating out of rooms on the second floor of downtown businesses and hotels.

Women like Ella Potts experienced the harsh consequences of being independent with no protection. Starting as a streetwalker, Potts faced frequent arrests and orders to leave town. When she attempted to establish her own house in Roosevelt township in April 1911, authorities responded severely.

Her bond was set at the enormous sum of $1,400 — clearly intended to keep her in jail. Unable to raise this amount, she remained in custody until her case reached the Grand Jury, which indicted her in September 1911. Her court appearance revealed her outsider status when she had to swear she was without means to procure an attorney and had "no friends from whom she could secure a loan."

The court appointed H.J. Lord to defend her, but the outcome was predictable — a $500 fine. Unable to pay, Potts chose to serve six months in the county jail. Ironically, this offered certain advantages: the jail was newer, providing warmth and decent meals, and as typically the only female prisoner, she at least had privacy.

ADVERTISEMENT

Comparing Towns: Hattie Fay in Mallard

Nearby Mallard offered a different picture of how vice operated in northern Minnesota. There, Hattie Fay — described as "dark-eyed, buxom, about 5-feet-7-inches, 140 pounds and good-looking in a hard sort of way" — ran her operation with different challenges than her Bemidji counterparts.

Hattie started with a simple tent near railroad tracks, with canvas walls hung from wire stringers forming makeshift rooms. She later upgraded to two small houses on land owned by F.O. Sibley, a local real estate agent. Each house accommodated three women, with modest prices of $1 for a brief visit and $5 for the night.

While Bemidji's madams cultivated political connections, Hattie's downfall came from unexpected directions: the town's women and her own customers. When Mallard wives discovered their husbands were visiting Hattie's establishment rather than playing whist at the Hart Lake lumber camp, they took direct action. The women tracked their husbands through marks they'd made on their overshoes and eventually, in spring 1906, burned down the houses themselves.

Later, in Bagley, when Hattie attempted to drug and rob lumberjacks with Mickey Finns, her customers took revenge, methodically dismantling her house with axes and saws until it was reduced to rubble — far from the political protection enjoyed by Bemidji's established madams.

The Migration: From Hill to Swamp

The closure of Bemidji's "Depravity Hill" district in 1904, followed by a major fire on Feb. 15, 1904, merely redistributed vice operations. Many moved west of town to the "Swamp House," while others scattered to neighboring communities or more discrete locations within Bemidji.

The Swamp House became particularly visible, being the first building passengers saw when arriving on the Soo and Great Northern lines from the west. Despite its prominence, it operated with a semi-official status. Records show that a woman in charge of a similar place on South Lake Irving would regularly appear in police court to plead guilty and pay a $100 fine plus costs — essentially purchasing monthly protection.

This arrangement drew protest from respectable citizens, particularly farmers living across Lake Irving. When Mayor Malzahn initially refused to act, citizens threatened to take complaints directly to the governor.

ADVERTISEMENT

The human toll became evident in tragic cases like Alice "Short Face Annie" Short. Initially running a "hotel" on 12th Street that was actually a bordello, she later moved to a farm west of Bemidji. Her suicide by hanging in 1912 at age 32 speaks to the psychological burden of the trade. Ironically, her husband Billy Short opened a new house halfway between Bemidji and Wilton shortly after her death.

By late 1912, enforcement patterns were shifting. When John Ryberg was arrested for running a disorderly house on Second Street, authorities focused on liquor violations and exploitation of women. The era of the grand brothel gave way to more discrete operations in downtown hotels, setting the stage for the challenges of the Prohibition era to come.

For more information about the Historical Society, visit www.beltramihistory.org.