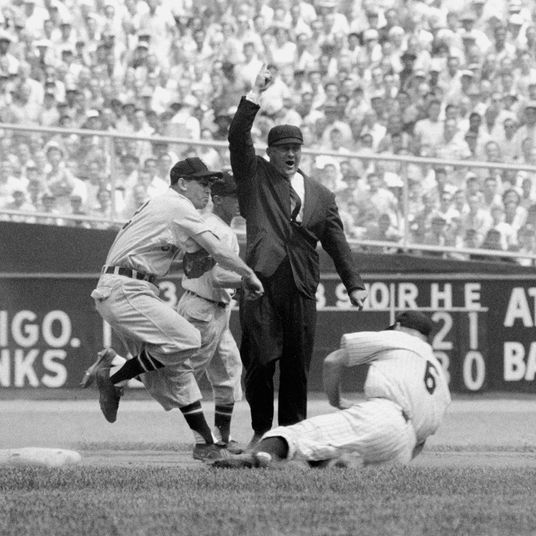

During a raucous city-election season 60 years ago, nearly everybody in New York agreed on two things: The city was going to hell in a handbasket, and something needed to be done about it. “I’m running a campaign that calls for change because change is needed,” liberal Republican congressman John Lindsay thundered in a debate against his Democratic opponent, comptroller Abe Beame. “There is one murder in this city every 14 hours, one rape every six hours, one theft every three minutes … 100,000 middle-income families have left New York City, 18,000 jobs a year. The city is near bankruptcy. There is no long-range fiscal planning and no program planning. And the administration of which Mr. Beame has been part and parcel has to shoulder the responsibility for this.”

It was true. Before becoming comptroller, Beame had been a top finance official in the three-term Democratic mayoralty of Robert Wagner, which had run its course and done little to tame, trim or transform a sprawling, sluggish, patronage-infested municipal bureaucracy. A third candidate in the race, conservative William F. Buckley, dubbed Lindsay a “flamboyant idealist” as a put-down, but Lindsay won by promising to apply strong medicine to agencies that clearly needed to be merged, eliminated, or overhauled. As columnist Murray Kempton put it, “He is fresh and everyone else is tired.”

New Yorkers picked the tall, good-looking WASP from the East Side and assigned him the mission of curing not just the visible and all-too-familiar urban problems of poverty, discrimination, troubled schools, and violent crime. Voters had also lost faith in the ability of political leaders and a sluggish, unresponsive bureaucracy to turn things around. A major, multipart investigative series on the city’s problems by the Herald-Tribune newspaper in 1965 opened with the memorable words: “New York is the greatest city in the world — and everything is wrong with it.”

In New York’s list of memorable, clearly consequential mayors like La Guardia, Koch, and Bloomberg, Lindsay is often given short shrift. Aside from a loop in Central Park and the newly refurbished East River Park, no major public buildings, parks, or structures bear the name of the mayor who brought New York air-conditioned subways; created the nation’s first 9-1-1 emergency call system; and signed the Rent Stabilization Act, which remains the city’s most important affordable-housing measure to this day. Those of us who lived in the city at the time are more likely to associate Lindsay with the many labor strikes and street riots that happened on his watch, along with a notoriously botched response to a blizzard in 1966 that left 42 people dead.

But Lindsay’s two tumultuous terms provide important lessons for this year’s crop of City Hall hopefuls in how to attack, and perhaps even slay, the stubborn dragons that are once again threatening to devour Gotham. (My three-part documentary series and panel discussion about the Lindsay years are online at You Decide, my podcast).

The first and most important lesson: Think big and swing for the fences. Shortly after his inauguration, Lindsay decreed the city’s bureaucracy a “pile of old rusty junk” and moved to consolidate 50 agencies into ten “superagencies,” forcing mergers by executive order when the City Council refused to go along. He created the Taxi and Limousine Commission, the Health and Hospitals Corporation and the nation’s first municipal Department of Environmental Protection and successfully pushed for the merger of the New York City Transit Authority with the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority to create the modern MTA. Importantly, Lindsay also established the 59 community planning boards that give citizens a voice in how development takes place as an alternative to the political clubhouses that controlled many neighborhoods.

Not every Lindsay reorganization was successful — a poorly conceived effort to simultaneously decentralize and desegregate city schools led to a paralyzing teachers’ strike — but today’s mayoral candidates should emulate Lindsay’s creativity and willingness to redraw the city’s org chart when necessary. Should the Department of Correction be merged with Probation? Mayors Giuliani and Bloomberg temporarily had both departments run by a single commissioner; perhaps the move should be permanent. Should the Rikers Island jail complex be placed under control of a federal court monitor? Mayor Adams fought against the takeover at every turn, even as the number of suicides, overdoses, and other deaths of people in custody on his watch has climbed to 37.

Do we need a separate, specialized agency tasked solely with addressing the complex needs of seriously mentally ill New Yorkers? And what about the idea, recently floated by Vital City, of empowering a single agency — not necessarily the NYPD — to be in charge of subway safety? If things in New York are as bad as today’s candidates keep telling us they are, they should be thinking in big, broad strokes, not just doing a little tinkering here and there.

The other big Lindsay lesson is his ability to attract and inspire men and women of extraordinary talents, many of them dubbed “whiz kids,” in their 20s and early 30s, whom the 44-year-old mayor entrusted with enormous power and responsibility.

Several of these well-chosen aides went on to extraordinary careers as elected officials, including H. Carl McCall (state senator and state comptroller); Ronnie Eldrige (City Council); Elizabeth Holtzman (congress, district attorney and city comptroller); and Lindsay’s human-rights commissioner, Eleanor Holmes Norton, who has been the elected delegate to Congress from Washington, D.C., since 1991. Many of the whiz kids went on to run major institutions: Lindsay’s chief of staff, Peter Goldmark, became the president of the Rockefeller Foundation and executive director of the Port Authority; another chief of staff, Steve Isenberg, became chairman of Newsday; press secretary Bob Laird became op-ed editor of the Daily News; and First Deputy Mayor Dick Aurelio launched NY1, the nation’s first 24-hour all-news cable channel. Jay Kriegel and Sid Davidoff became the kind of behind-the-scenes fixers who spent decades nurturing, connecting, and representing all manner of public and private institutions.

Lindsay’s bench wasn’t just built on luck or Ivy-League personal connections. According to Goldmark, top hires went through an exhaustive gauntlet of interviews and background checks to assess who was hungry, smart, honest, and willing to work long hours, a process he learned from Fred Hayes, a budget expert Lindsay poached from the Johnson administration.

“It was fun to be with them because they were energetic and they had a lot of ideas, and they were doing things and they loved their work,” Holtzman told me. “They admired the mayor, and they all thought they were doing God’s work in the city”

“I think all of us must have felt at some point some nagging feelings that maybe we weren’t old enough, wide enough, broad enough, deep enough. But hell, we were in it. We were going to give it all we got, and he trusted us,” Isenberg later recalled. “You went to work every day with the most wonderful illusion you can ever have: That you could make a difference for the city.”

That kind of energy, idealism, and reform spirit has been lacking in the Democratic primary campaign so far. But with just under 90 days to go, it’s not too late for us all to demand that the candidates talk about major structural changes rather than small adjustments and that they promise to find the very best people to run the city’s agencies and turn them loose to do God’s work in a city that, 60 years after Lindsay, is in crisis once again.

More city politic

- Columbia University Must Choose Between Courage and Cowardice

- The Race to Outrank Cuomo

- Adrienne Adams Says She ‘Cannot Sit Back and Do Nothing’