As new, potentially deadly substances enter street drug supplies, a Pennsylvania program tracks changes in real time

PA Groundhogs and the Center for Forensic Science Research & Education monitor for novel and emerging substances by testing submitted street drug samples.

Listen 3:53

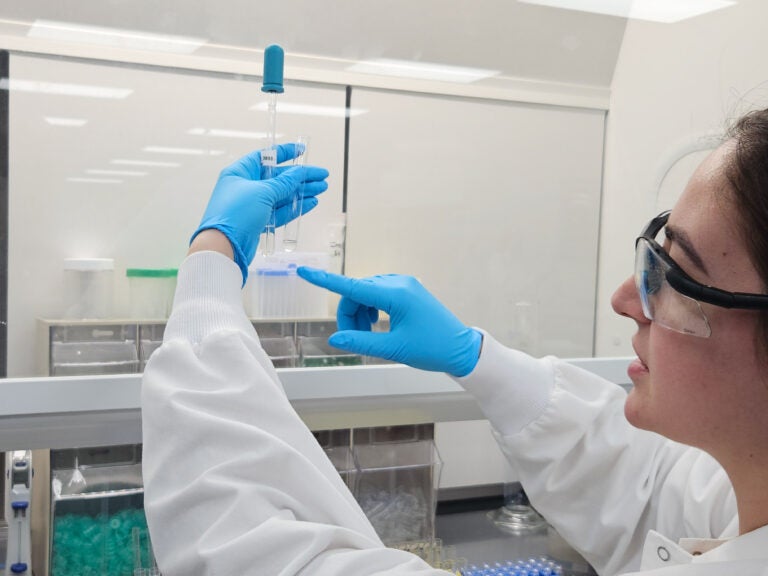

Alexis Quinter, a forensic chemist at the Center for Forensic Science Research and Education in Horsham, Pennsylvania, performs an extraction process on a batch of drug samples from Trenton, New Jersey, sent to the lab through PA Groundhogs. The process extracts a purer version of the drug sample and filters out the “gunk,” or particles like starches and sugars that might be mixed up with the drug compound that scientists want to analyze. (Nicole Leonard/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Inside the laboratory at the Center for Forensic Science Research & Education in Horsham, chemists and toxicologists are surrounded by loud, whirring machines connected to various tubes, wires and beakers used to analyze solids and liquids.

The substances they’re testing are often sold illegally in tiny bags or packages. Now, they’re being examined under bright fluorescent lights, dissolved in liquid and injected into test tubes.

“These are all of our GC-MSs, so gas chromatograph mass spectrometers,” explained Alex Krotulski, a forensic toxicologist and lab director at the center, while pointing at a row of instruments on a lab work bench.

On the top of one machine, tiny glass vials containing illicit drugs dissolved in a liquid solution are in a carousel that rotates them under a syringe, which punches down into the vial tops and extracts a sample for the mass spectrometer.

“All of the drug powders, pills, plant materials, liquids, anything that comes through goes through analysis on this instrument,” Krotulski said.

The lab processes and analyzes thousands of samples every year. City and state health departments, hospitals, coroner’s offices and drug treatment centers from all over the country send in solid substances and biological specimens, such as blood and urine for testing.

What makes the lab different from crime laboratories or other academic research centers is that it specializes in documenting illicit and addictive substances found in local street drug supplies and markets.

Street drugs are a volatile mix of potentially lethal substances, with new ingredients entering the scene at a fast pace.

In cities like Philadelphia, overdose deaths from synthetic opioids like fentanyl are down, but other noxious adulterants are constantly infiltrating the street drug supply.

In a collaboration between the Center for Forensic Science Research & Education and PA Groundhogs, a Pennsylvania drug checking organization, experts are working to analyze these changes in real time and quickly identify novel substances that may pose new overdose risks or health complications among people living with addiction.

“It’s 2025. We’ve got the technology, we’ve got all the infrastructure in place, so that information can become readily available,” Krotulski said.

Expansion of testing for street drugs

PA Groundhogs launched in 2023 shortly after the Pennsylvania legislature and Gov. Josh Shapiro passed a state law that legalized drug checking technology for the purpose of harm reduction efforts.

The organization distributes tools like test strips for fentanyl, xylazine and benzodiazepines. The group also provides free drug testing kits to public health agencies and harm reduction workers, who can submit street drug samples to the laboratory in Horsham.

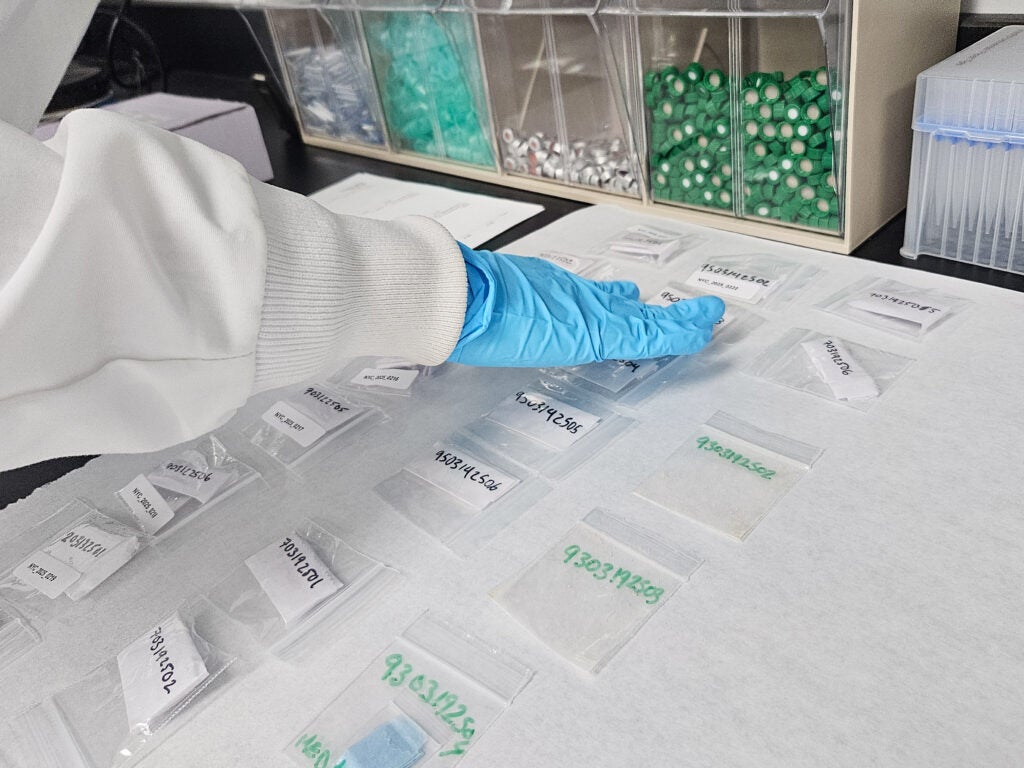

Little baggies, packets and envelopes filled with powders, pills and drugs in other forms are shipped or delivered to the lab anonymously. PA Groundhogs founder Christopher Moraff said this is to protect participating groups and organizations that are handling Schedule I controlled substances.

A large portion of local drug samples come from the Philadelphia and Pittsburgh areas, but others come from at least 25 Pennsylvania counties and, more recently, from Trenton, New Jersey.

In its first full year of operations, PA Groundhogs helped process more than 645 street drug samples, according to a new annual report.

Moraff, who has documented the effects of the opioid crisis on communities like Kensington as a journalist and documentary producer, said real-time testing results can help communities better identify new and potentially deadly substances — the next fentanyl or the next xylazine.

The data, which is routinely posted and updated in an online database, can also help explain why some people might show up to an emergency room with new health complications.

“It’s helpful for the clinicians to know what they’re dealing with,” Moraff said, “which in a lot of cases, they don’t.”

Real-time tracking and data

Historically, street drugs may get tested by crime labs when they’re related to an open investigation or death. But Moraff said those samples might not get processed for months if there are backlogs.

Meanwhile, changes in the street drug supply can happen much more quickly.

That’s where the Pennsylvania street drug checking program and collaboration can help experts direct more resources and funding to specific harm reduction strategies that target emerging drugs or substances, Moraff said.

For example, more street opioids in Philadelphia are being cut with a veterinary sedative called medetomidine.

“Over the past month or so, people have been reporting adverse events, feeling different, stronger sedation,” Moraff said. “So, to be able to present that information to harm reduction groups, for instance, to share with their participants, to be able to present it with clinicians, we’re doing it as close to real time as possible.”

Some drug samples have contained BTMPS, a harsh industrial chemical that doesn’t look like other kinds of drug molecules under a microscope, which can make it difficult for the average laboratory to catch.

But the Center for Forensic Science Research & Education has state-of-the-art instruments, digital libraries of drug and chemical compounds and scientists who can identify and quantify the smallest or most novel components in any given sample.

Interest in the PA Groundhogs program is growing among health providers, law enforcement and harm reduction groups, Moraff said, as everyone tries to get ahead of an ever-changing street drug supply and prevent more harm from coming to people struggling with addiction.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.