India is a union of 28 states (provinces). The population in some of these states is bigger than that of the largest European countries. For example, Uttar Pradesh is home to more than 240 million people, almost three times the population of Germany. Although a part of a federal union, every state has a unique history, shaped by its environment and natural resources, princely or British colonial heritage, language and culture. Since the end of British rule in the region in 1947, their economic trajectories have diverged, too.

With roughly 35 million people, Kerala, which sits along India’s southwestern tip on the Indian Ocean, is among the smaller Indian states, though it is densely populated. In the 1970s, Kerala’s average income was about two-thirds of the Indian average, making it among the poorest states in India. This difference persisted through the 1980s. In the coming decades, a miracle occurred. Kerala, one of the poorest regions in India, became one of the richest. In 2022, Kerala’s per-capita income was 50-60 per cent higher than the national average. What happened?

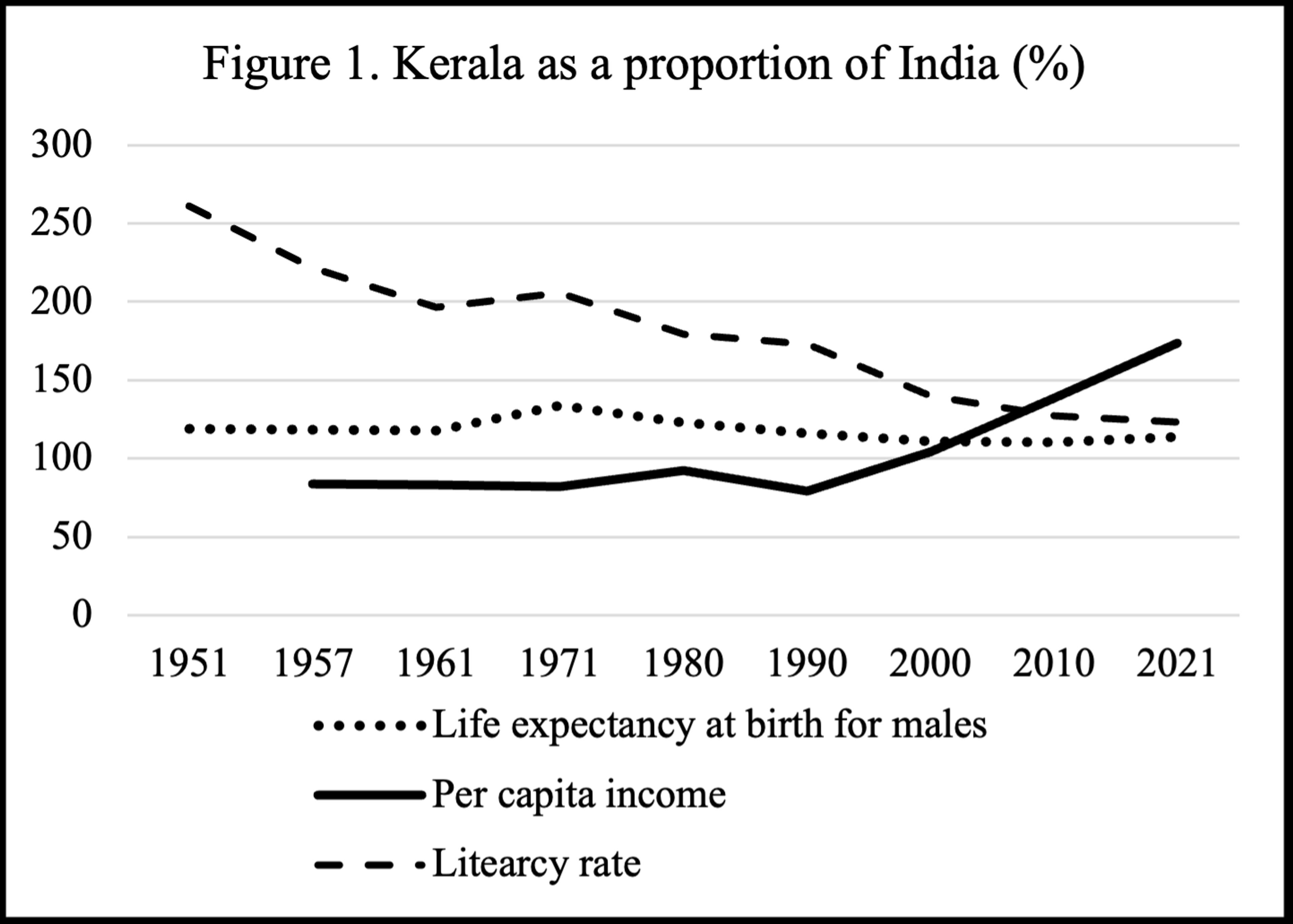

Even when it was poor, Kerala was different. Though income-poor, Kerala enjoyed the highest average literacy levels, health conditions and life expectancy – components of human development – in all of India. Among economists in the 1970s and ’80s and among locals, ‘Kerala is different’ became a catchphrase. But why, and different from whom? One big difference Kerala presented was with North India, which had an abysmal record of education and healthcare. While the population grew at more than 2 per cent per year in the rest of India, Kerala’s population growth rates remained significantly lower in the 1970s. High literacy and healthcare levels contributed to this transition.

Kerala’s unusual mix of high levels of human development and low incomes drew wide attention, including from leading scholars. Among the most influential writers, K N Raj played a big part in projecting Kerala as a model for other states. Anthropologists like Polly Hill and Robin Jeffrey drew attention to some of the unique features of the society that led to these achievements. In a series of influential works, the Nobel-laureate Amartya Sen and his co-author the economist Jean Drèze praised Kerala’s development model for prioritising health and education, even with limited resources, and claimed that this pathway led to significant improvements in quality of life. Kerala vindicated the intuition that Sen and others held that health and education improved wellbeing and shaped economic change by enhancing choices and capabilities.

Why do Kerala’s differences matter? What lessons did the economists draw from the state’s unique record? Around 1975, India’s economic growth had faltered, and a debate started over whether the country should give up its socialist economic policy in favour of a more market-oriented one, in which the government would take a backseat. Kerala suggested three lessons for those engaged in the debate: (a) income growth rate was a weak measure of standards of living; (b) what mattered was quality of life, including education, good health and longer lives; and (c) the government was necessary to ensure investment in schools and hospitals. The three lessons would coalesce into the Kerala Model, an alternative recipe for development to the neoliberal model then being pushed by Right-wing lobbies.

But Kerala was about to grow even more different, confounding orthodoxies in political science and economics. In the 2000s, average income in the state forged ahead of the Indian average. Compared with Indian averages, the post-1990 growth record was less impressive regarding human development, as India caught up with Kerala (see graph below). The forging-ahead in income was offbeat and is still poorly understood. This question remains unanswered because, so far, the attention of economists has been elsewhere – welfare policies – whereas the income turnaround suggests an emerging pattern of private investment that strides in basic health and literacy alone cannot explain.

Before we tackle that question, it will be useful to discuss the huge presence of the state in development studies. Where does it come from? Why does the state fascinate so many social scientists?

From a historical perspective, Kerala has at least four distinct qualities that most states in India do not share. First, it has a centuries-long history of trade and migration, particularly with West Asia and Europe. Second, Kerala is rich in natural resources, which have been commercially exploited. Third, Kerala boasts a highly literate, skilled and mobile workforce. Finally, the state has a strong Left political movement. Any story we tell about its advances in health and education or its recent income growth must refer to some of these longstanding variables.

Why was Kerala different? In the minds of many economists, the state’s heritage of Leftist trade unions (more on this later) and successive rule by Leftist political parties helped provide the foundation for strong human development. Socialism was not just a popular ideology but had a real chance to deliver in this state. Others stressed geography, princely heritage and social reform movements. For example, the British anthropologist Polly Hill noted that Kerala differed due to its coastal position, semi-equatorial climate, maritime tradition, mixed-faith society and princely rule. The combined share of the population following Islam and Christianity in Kerala is about 45 per cent; for India as a whole, it is 16.5 per cent. The state is home to one of the oldest branches of Christianity. Further, the strategic location along the Arabian Sea facilitated interactions with traders worldwide, including Arabs, Europeans and others. The local rulers were generally tolerant of diverse religious practices.

Many economists in Kerala who noted the difference did not think there was much reason to celebrate. Some said that the record on healthcare and education hid a profound inequality from view. Others said the low and stagnant income pushed the state’s fiscals into bankruptcy, making the model unsustainable without active markets driving investment and income growth. By the 1990s, the model’s limitations became apparent as the state struggled with low economic growth and financial strains.

If the situation did not lead to a severe crisis, this was due to inward remittances. The state had a long history of labour migration, with significant numbers of people moving to the rest of India and the Persian Gulf states for work. This migration led to substantial remittances, which sustained private consumption, income and investment. By 2010, the excitement over the Kerala Model was dead, and incomes started forging ahead.

The Left changed their focus from land and educational reforms to private investment and decentralisation

The economists (above) who joined the developmental debate took Kerala’s income poverty for granted. They neither saw the income growth coming nor were prepared to explain it. Some Left-leaning economists attributed the resurgence in per-capita income to education and healthcare. But this is not persuasive. A surge in economic growth everywhere and at all times implies rising investment in productive capital, and basic education and healthcare would not deliver that.

The Indian economy in the 2000s saw robust investment and economic growth. But Kerala was not a major destination for mobile private capital. The forging ahead owed to more specific factors, some more peculiar and powerful than those driving India’s transformation.

Here, we must return to Kerala’s historical engagement with the world economy, its natural resources, its literate workforce and its distinctive political landscape. In different ways, all these reinforced private investment. Deep connections with the global economy were pivotal to the recent history of labour migration. While migration created a flow of remittances into consumption, another significant flow went into investment, especially in service sector enterprises in healthcare, education, hospitality and tourism. The state’s temperate semi-equatorial climate, mountainous topography and abundant water resources supported plantations and natural-resource extraction and processing industries for centuries. Some declined in the mid-20th century, but investment in these activities revived later.

The communist movement in Kerala began in the 1930s with the formation of the Congress Socialist Party, driven by peasant and labour movements and anticolonial struggles. The movement joined electoral politics after the formation of the state in 1956, and since then, Left-ruled governments have formed from time to time, almost always with coalition partners. The Leftist political movement in Kerala helped shape the state’s economic policies. In recent years, the Left also changed their focus from land and educational reforms to private investment and decentralisation. Capable local self-government institutions strengthened democratic governance.

In short ways, four forces of change – Kerala’s reintegration with the global economy, remittances from the Persian Gulf, strong welfare policies from a legacy of Leftist government, and private investment from individuals and businesses who shared the remittance flows – have combined to form the structure of Kerala’s miracle of human wellbeing with economic growth.

Around 1900, Kerala was a region composed of three political units: the princely states of Travancore and Cochin, and the British Indian district of Malabar. There were a few other smaller princely states as well. There was a broad similarity in the geography across the three units. India’s climatic-ecological map will show that all of Kerala is a semi-equatorial zone with exceptionally heavy monsoon rains, whereas most of India is arid or semi-arid tropical. The region has plentiful water and almost no history of famines, unlike the rest of India.

Geologically, too, Kerala was distinct. The mighty Western Ghats mountain range runs along its eastern borders throughout. Although the southwestern coast offered little scope for agriculture because good land occurred in a narrow strip between the sea and the mountains, the uplands produced goods like black pepper, cardamom, cloves, cinnamon and ginger, which had a ready demand in the world market. Plentiful coconut trees offered scope for coir rope manufacture. The climate was suitable for rubber and tea plantations. The sailing ship construction industry on the western coast obtained timber from the Malabar forests. In the present day, plywood is a major industry.

In the interwar period, poorer and deprived people circulated more

Around 1900, the authorities in all three regions helped foreign capital, which produced or traded in plantation crops like coffee, tea and pepper, and forest-based industries including timber, rayon, coir and rubber. Some of these products were traded globally. These businesses relied heavily on local partners and suppliers, which led to the accumulation of wealth in the hands of groups like the Syrian Christians.

Some of this wealth was invested in small-scale plantations and urban businesses, which encouraged the local migration of agricultural labourers. In the interwar period, poorer and deprived people circulated more. They sought work outside traditional channels like agricultural labour where they had been at the beck and call of upper castes or caste Hindus. At the same time, protestant missions, social reformers and Leftist political movements became active in ameliorating their conditions. These forces led to a significant focus on mass education. The princely states stepped into mass education late but with greater resources on average than a British Indian district. Their investment reinforced the great strides in health and education that made Kerala different.

Nine years after India gained independence, Malabar merged with Cochin and Travancore to form the Kerala state. At that time, the livelihoods in the region, like the rest of the country, were based on agriculture. However, a much larger proportion (half or more) of the domestic product was urban and non-agricultural, compared with India as a whole. Nearly 40 per cent of the workforce was employed in industry, trade, commerce and finance, compared with 20-35 per cent in the larger states in India.

One reason for this was the scarcity of farmlands. The state’s mountainous geography made good land extremely scarce. The exceptionally high population density in the areas of intensive paddy cultivation ensured a level of available land per head (0.6 acres) that was a fraction of the Indian average (3.1 acres) around 1970, and low by any benchmark. Paddy yield was high in these areas. Still, with the low size of landholding, most farmers were families of small resources.

Urban businesses processing abundant natural resources were another story. Some of these businesses were small, non-mechanised factories processing commercial products like coir in Alappuzha (Alleppey) and cashew in Kollam (Quilon). Some areas, such as Aluva (Alwaye), had larger, mechanised factories producing textiles, fertilisers, aluminium, glass and rayon. The region also had tea estates in the hills, and rubber and spice plantations east of Kottayam. Kerala today is a leading region in Indian financial entrepreneurship. Businesses from the region established banks, deposit companies and companies supplying gold-backed loans, which have a presence throughout India. Several of these companies emerged in the interwar period to finance trading and the production of exportable crops.

Thrissur (Trichur) and Kottayam were service-based cities with a concentration of banks, colleges and wealthy churches. Most local businesses were small-scale, semi-rural and household enterprises. Foreign multinationals owned tea estates and export trading firms at the apex of the spectrum of firms. Nearly everything else – from banks to small plantations, trading firms, agencies, transport and most small-scale industries – were Indian-owned family businesses.

Before statehood began in 1956, a powerful communist movement had emerged

From this base, the two decades after 1956 saw a retreat of private investment from industry and agriculture. Partly because of adverse political pressure, the foreign firms left the businesses, and plantations changed ownership. A militant trade union movement rose in the coir- and cashew-processing industries, and most firms, being relatively small, could not withstand the pressure to raise wages. Some shifted operations across the border with Tamil Nadu, where the state did not protect trade unions and labour costs were cheaper. With the central government’s heavy repression of private financial firms and the retreat of private banks, the synergy between industry, banking and commerce was broken. Private capital retreated from industrial production and trading. Following the socialist trend present in India in the 1960s, Kerala state invested in government-owned industries, which were inefficiently managed and ran heavy losses, usually resulting in negative economic contributions.

Private investment in agriculture declined, too. The Left political movement, which was concentrated in agriculture, was again partly responsible. Before statehood began in 1956, a powerful communist movement had emerged. The movement’s leaders understood that inequality in this part of India was not based on class alone. The agricultural countryside was characterised by inequality between the landholders and landless workers, which was only partly based on landownership but also drew strength from oppression and deprivation of lower castes by upper castes.

A narrow strip of highly fertile rice-growing plains in the central part of the state was the original home of Leftist politics. From the 1940s, it was a political battleground. The Leftist political parties organised the poorest tenants and workers into unions. Class-based movements to get higher wages, better employment terms or more land merged with movements to achieve equal social status. The agricultural labourers came from the depressed castes so they were interested in both class and caste politics.

When in power for a second time (from 1967), the communists ruling in coalition delivered on a promise made long ago: radical land reform. The policy involved taking over private land above a ceiling, redistributing it to landless workers, and bringing them under trade unions. The policy was successful in the extent of land redistributed (compared with most states that followed a similar policy) and in sharply raising wages. However, it did have a damaging effect on investment.

Many employers migrated to the Persian Gulf, leaving their land unattended

From the 1970s, private investment withdrew from agriculture. The cultivation of tree crops held steady, if on a low key. But cultivation of seasonal field crops, especially paddy for which the lowlands and the river basins were especially suitable, fell throughout the 1980s. By 1990, traditional agriculture was reduced to an insignificant employer and earner, and for most people still engaged in it, the land provided no more than a subsidiary income. A relative retreat from traditional agriculture is not unique to Kerala, it happened all over India. But in Kerala, the fall was spectacular.

In this densely populated area, the average landholding was small. Most landholders were middle-class people and not particularly rich. The policy squeezed their resources. Investment and acreage cropped fell. Those who remained tied to land did so because they had nowhere to go or worked the land mainly with family labour. The first Green Revolution unfolded in the rest of India, including Tamil Nadu, and had little impact on the state. Many employers migrated to the Persian Gulf in the late-1970s or ’80s, leaving their homesteads and the land unattended. What made all this anomalous was the high unemployment rate in the countryside, possibly the highest in the country. How were high wages and the retreat of a significant livelihood possible in this condition?

The answer is Gulf remittance. Hundreds of thousands of people migrated to the Persian Gulf states like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Qatar to work in construction, retail and services, sectors that saw a massive investment boom following the two oil shocks of 1973 and 1979. As they did, the money from the Gulf flowed into construction, retail trade, transport, cinema halls, restaurants and shops in Kerala. An emerging service sector labour market absorbed the effort of those who had been made redundant in agriculture or did not want to work there anymore.

What drove emigration to the Gulf? And why did Kerala lead the emigration of Indians to the Gulf? One answer is that the region had for centuries deeper ties with West Asia than any other part of India. Also, high unemployment pushed skilled individuals to seek work outside the state. Kerala, for at least three decades (1975-2005), supplied a significant share of the workers who moved to these labour markets. The demand for skilled workers increased as the Gulf economies diversified from oil-based jobs to finance and business services. While offering jobs in the millions, the migration also had a series of broad effects back home on occupational diversification, skill accumulation, changing gender roles, consumption, economic and social mobility, and demographic transitions.

In the 1990s, the Indian economy liberalised, reducing protectionist tariffs and restrictions on foreign and domestic private investment. In the following decades, increased private investment led to generally elevated economic growth rates. At the same time, the political culture shifted away from emphasis on socialist ideas, becoming more market-friendly than before. Kerala was not untouched by these tendencies, but its specificities – natural resource abundance, Leftist legacy, migration history – joined the pan-Indian trend distinctly. There were three prominent elements in the story.

First, a demographic transition completed by 1990, when population growth decreased substantially. The fall in population growth rate was not unique to the state but aligned with broader Indian trends. However, the levels differed. Of all states in India, Kerala was ageing much faster than the rest and from earlier times.

Second, politics changed. Again, the legacy of Left rule was an important factor behind the shift. A communist alliance won the first state assembly elections in 1957, lost in 1960, returned to power and ruled the state in 1967-70 (with breaks), 1970-77, 1978-79, 1980-82, 1987-91, 1996-2001, 2006-11, and since 2016. The composition of the Left coalition changed multiple times, never consisting only of ideologically Left parties. It included, for example, the Muslim League and some Christian factions allied with the communists. However, until 1964, the main constituent of the coalition was the Communist Party of India (CPI), called CPI (Marxist), or CPI (M), after 1964. In no other state in India, except West Bengal (and later Tripura), did the CPI/CPI (M) command a popular support base large enough to win elections.

The Left turned friendly towards private capital and shed the rhetoric of class struggle

The Left Democratic Front, which had ruled Kerala in different years, returned to power in 2016 and has been in power since then. In the 2000s, the Leftists quietly reinvented themselves. They needed to because the older agenda was almost dead. In elections in the 1960s and ’70s, agricultural labourers in this land-poor state formed the main support base for communist victories based on the promise of land reforms. Caste-equality social reform movements coalesced around the Leftist movement. After the Leftists delivered land reforms, there was not much of an agenda.

From 2000, the Left turned friendly towards private capital and shed the rhetoric of class struggle. In practical terms, the state retreated from regulating private capital and strengthening trade unions, and focused on infrastructure investment to strengthen small businesses. The reinvention was a success and delivered election victories. As the private sector took charge of investment in education and healthcare, the state could afford to focus on decentralised governance, corruption-free administration, improved public services and urban infrastructure. The class-based politics of the 1960s and ’70s died. With private investment rising, the state had more capacity to fund welfare schemes and public administration. Tourism promotion is an excellent example of a new form of synergy: the state builds roads, private capital builds hotels, and lakes and mountains supply the landscape.

Third, investment in Kerala revived. Over the past three decades, the private sector has increasingly driven education and healthcare. Since 1990, many new types of small-scale businesses have flourished in the state. There is no single story of where the money came from and what these enterprises add to employment potential. We know much of it happened on the back of natural-resource processing. In all fields, value was added by accessing niche export markets, using new technologies, and forming many micro, medium and small enterprises. The state has one of the highest concentrations of startups. Natural resource extraction does not mean any more plantations packaging harvested spices but the extraction of nutraceuticals. Jewellery manufacture involves invention and experimentation with designs. Rubber products diversified from automotive tyres to surgical accessories.

Although foreign investment inflow, which supported business development in the princely areas, was revived via the Gulf route, most of the business development is concentrated in non-corporate family firms. Few raise significant equity capital or are publicly held. Most service sector enterprises in tourism, trade, transport, banking and real estate are relatively small. Family business remains a strong organisational model. Little research exists on the externalities that these businesses generate. The one large exception to this rule is investment in IT clusters near the big cities.

Let us start with a restatement of the main points of the story. Not long ago, Kerala was celebrated for its exceptional human development indices in education and healthcare, with many scholars attributing this to an enlightened political ideology and communist influence. These advances also resulted from factors like the princely states’ higher fiscal capacity, favourable environmental conditions, and a globally connected capitalism. During the 1970s and ’80s, government interventions weakened market activity and growth, making human development look even more striking than otherwise. Since previous commitments to social infrastructure were maintained, the state was heading toward a fiscal crisis.

In the 2000s, an economic revival came through mass migration and remittances, initially supporting consumption and construction. At the same time, a wealthier and technically skilled diaspora invested in the state, in services and manufacturing. New sectors like tourism, hotels, spice extracts, ayurvedic products, rubber products and information technology drove this revival. Remittances also flowed into new forms of consumption. The urban landscape transformed, with towns developing shopping malls, restaurants and modern businesses. While earlier regimes discouraged private investment, now there is a symbiosis between the private sector and the state, as market activity supports public welfare commitments.

The New Left, unlike the Old Left, is open to private capital and acknowledges the importance of the market, including the global market. Without compromising welfare expenditure, the state has expanded the hitherto neglected infrastructure projects, crowding in private investments. This is the second turnaround in the development trajectories of the state. The first turnaround happened during the early 1980s fuelled by remittance money. The second turnaround happened in the 2010s, when social growth, always Kerala’s strength, joined unprecedented levels of capital expenditure. If both the Left and non-Left political parties could take credit for the first turnaround, the credit for the second one should rest with the New Left.

Recent climate change and overdevelopment have increased disaster risks

Looking forward, the pathway of recent economic change has both strengths and challenges. The strengths include the generally high quality of life in small towns, improved youth aspirations often marked by an increased flow to foreign universities, better worker safety, the ability to attract skilled and unskilled migrants, unique natural-resource advantages and a degree of sociability in relations between castes and religions. The challenges are poor higher education quality, environmental threats from new forms of tourism infrastructure and climate change, a rapidly ageing population, and the possibility of a fiscal crisis.

Some of these challenges are enormous, and are already straining the budget and state capacity. Land reforms brought some equality, but the absence of follow-up actions prevented productivity improvements. Kerala produces less than 15 per cent of its food requirements, and relies heavily on central supplies and neighbouring states. To respond to this problem, the government has strengthened its public distribution system. That, along with the care of the elderly and scaling up of public services, particularly education and health, will place enormous burdens on the state’s public finances in the near future.

Historically, the state’s unique climate with abundant rainfall provided natural advantages, supporting high life expectancy and diverse agricultural opportunities. However, recent climate change and overdevelopment have increased disaster risks. The environmental transformation has been primarily driven by private construction, especially Gulf-funded developments in dwellings, hotels and service sectors. Land has become the single most speculative asset of the real-estate lobbyists. Extensive economic activities in ecologically sensitive regions, possibly accompanying tourism development with its tagline of ‘God’s own country’, allegedly led to landslides, soil erosion and environmental vulnerabilities. In recent years, an accent on ‘responsible tourism’ has tried to reduce the potential risks.

There is more. Human-wildlife conflicts and soil erosion have increased, and declining rainfall poses significant challenges. The devastating floods in 2018 and the near-disaster in 2019 highlighted the consequences of excessive construction and poor environmental management. The state now has one of India’s highest levels of consumption inequality. The quality of higher and technical education remains poor, contributing to educated unemployment.

The state’s future success will depend on balancing economic growth with environmental sustainability, improving the quality of education, improving the employability of graduates, and social equity. It is a complicated task precisely because so much of the recent growth owes to exploiting the environment. There is a real prospect of worsening inequality along caste, class, gender and age lines if the current pattern of growth slows. On the other hand, recent advancements in the digital and knowledge economy, combined with sustainable infrastructure, open fresh spaces for egalitarian development. Still, the future is hard to predict because the regional economy is deeply dependent on integration with the world economy and the ever-changing ideological alliances.