Student Absences Have Surged Since COVID. Some Lawmakers Say Parents Should be Jailed

Dozens of bills nationwide seek to address chronic absenteeism. While some focus on supports and incentives, others look to leverage punishments.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

As educators nationwide grapple with stubbornly high levels of student absences since the pandemic drove schools into disarray five years ago, Oklahoma prosecutor Erik Johnson says he has the solution.

Throw parents in jail.

Chronic absenteeism nearly doubled — to about 30% — the year after the pandemic shuttered classrooms, plunged families into poverty and led to the deaths of more than 1 million Americans. Student attendance rates have improved by just a few percentage points since the federal public health emergency expired nearly two years ago, a reality that’s been dubbed “Education’s long COVID.”

But Johnson, a Republican district attorney representing three counties in southeast Oklahoma, said the persistent absences have nothing to do with the pandemic and instead are because “we’re going too easy on kids” and parents have been given “an excuse not to be accountable.”

Since Johnson was elected in 2022 on a campaign promise to enforce Oklahoma’s compulsory education law, he’s forced dozens of students and parents into hasty court appearances and, on several occasions, put parents behind bars in the hope it will compel their children to show up for class.

Lawmakers nationwide have taken a similar approach, including in Indiana, Iowa and West Virginia, where new laws leverage the legal system to crack down on student absences.

“We prosecute everything from murders to rape to financial crimes, but in my view, the ones that cause the most societal harm is when people do harm to children, either child neglect, child physical abuse, child sexual abuse, domestic violence in homes, and then you can add truancy to the list,” Johnson said.

“It’s not as bad, in my opinion, as beating a child, but it’s on the spectrum because you’re not putting that child in a position to be successful,” continued Johnson, who has dubbed 2025 the “Year of the Child.”

Since the pandemic, policymakers have taken on a heightened role in addressing persistent student absences, and lawmakers nationwide have proposed dozens of bills this year to combat chronic absenteeism, typically defined as missing 10% of school days in an academic year for any reason. Such efforts have fallen broadly into two camps: incentives and accountability. States like Indiana have taken a similar approach to Johnson’s, imposing fines and jail stints for missed seat time. Other efforts have focused on addressing the root causes of chronic absenteeism, like homelessness, and have sought to draw kids to campuses with rewards.

In Hawaii, for example, pending legislation seeks to entice student attendance with the promise of free ice cream. In Detroit, where 75% of students were chronically absent last year, the district employs both the carrot and the stick: handing out $200 gift cards to 5,000 students with perfect attendance while warning those with an extremely high number of absences that they can be held back a grade in K-8 or made to repeat classes in high school.

In Oklahoma, where parents can be jailed for up to five days and fined $50 each day their child is absent from school without an excuse, proposed legislation would let schools off the hook.

For years, Oklahoma schools have received poor grades for chronic absenteeism, one metric the state uses to gauge school performance. If approved, the bipartisan bills would strike chronic absenteeism from the state accountability system, a change officials said is necessary because it’s the responsibility of parents — not principals and teachers — to get kids to class.

Schools in Oklahoma “have very little control over whether or not a kid gets to school,” Rep. Ronny Johns, a Republican from Ada, told The 74. Ada, the county seat of Pontotoc County, is ground zero for Johnson’s truancy initiative, an effort that Johns, a former school principal, said should be replicated statewide.

“We can encourage them to get their kids to school and everything,” Johns said. “But in the end, parents have got to get their kid up and get them to school.”

‘A shared responsibility’

The latest national data on chronic absenteeism, collected by the U.S. Department of Education for the 2022-23 school year, found that some 13.4 million students — nearly 28% — missed 10% or more of the academic year. In a majority of states, chronic absenteeism has shown marginal improvements since its peak. Nationally, chronic absenteeism reached an all-time high in the 2021-22 school year of nearly 30%. Pre-pandemic, the national rate was about 15%.

Some states like Colorado and Connecticut have seen substantial improvements in absenteeism, the data show. In others, including Oklahoma, absenteeism has gotten worse since 2021-22. In 2023, nearly a quarter of Oklahoma students were chronically absent, according to the federal data.

Chronic absenteeism is particularly acute among Native American, Pacific Islander, Black and Hispanic students, as well as those who are English learners, in special education or live in low-income households.

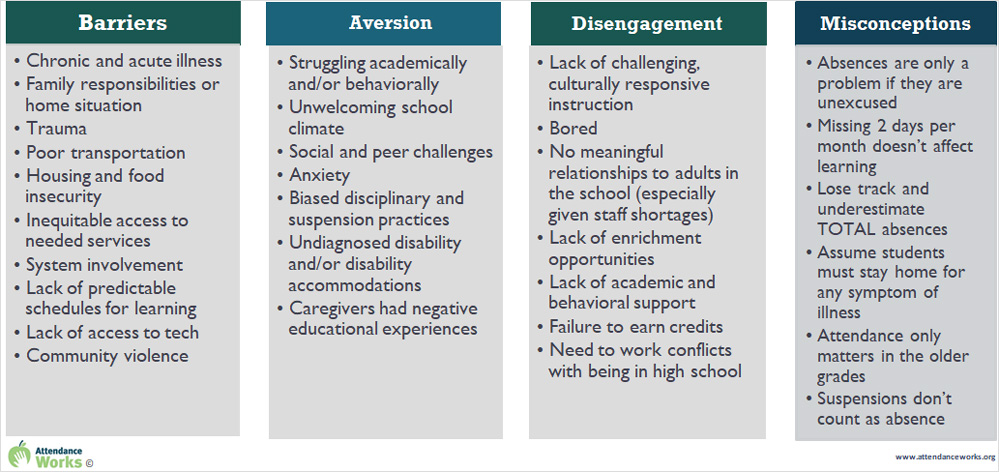

Hedy Chang, the founder and executive director of the nonprofit Attendance Works, said the key to solving chronic absenteeism is to address the underlying problems that make kids absent in the first place. The California-based nonprofit focused solely on improving student attendance identifies a range of “root causes”, including student disengagement, boredom and unwelcoming school climates. Caregivers’ negative education experiences are a factor, according to the nonprofit. So, too, is homelessness and community violence.

Last year, lawmakers in 28 states proposed at least 71 bills focused on identifying, preventing and addressing chronic absenteeism, according to analyses by the nonprofit FutureEd. This year, legislators in 20 states are weighing at least 49 bills focused on chronic absences, including efforts to improve data collection and create early interventions.

The Oklahoma legislation seeks to replace chronic absenteeism in its school accountability system with an alternative, such as a climate survey, a softer measure that would gauge students’, parents’ and educators’ opinions about their schools. The move would require approval from the U.S. Department of Education.

States have been required to collect chronic absenteeism rates since the passage of the federal Every Student Succeeds Act in 2015. Since then, chronic absenteeism has been included as one of six school performance indicators on Oklahoma’s annual A-F report cards from the state education department. Currently, 38 states use chronic absenteeism to grade school performance, Chang said.

For schools in Oklahoma, the measurement has proven to be a hurdle. In 2022-23, the state’s schools received an F grade in chronic absenteeism. Last year, the state grade ticked up slightly — to a D.

Removing chronic absenteeism from the state accountability system, Johns, the state lawmaker, said, could allow schools across Oklahoma to receive better grades. Meanwhile, he supports initiatives to handle student absences through the courts, arguing that “parents need to have some skin in the game.”

“Chronic absenteeism is driving our report card down,” Johns said. “Without the chronic absenteeism [measurement], our report card is not going to look as bad as it is because our public schools are doing some really good things, so why shouldn’t the report card be a reflection of that?”

Chang argued the move is misguided. She pointed to a growing body of research that has found schools can combat absenteeism if they form meaningful relationships with parents and partner with social services agencies that address underlying barriers to attendance, like food insecurity.

There’s little research to suggest that fines and other forms of punishment improve attendance. Even as some states ramp up truancy rules, others have scaled them back as studies report that punitive measures can backfire. In South Carolina schools, for example, students placed on probation for truancy wound up with even worse school attendance than they had before the courts got involved, according to a 2020 report by the nonprofit Council of State Governments Justice Center.

In a report published last year, the Oklahoma State Department of Education highlighted school districts that have made “impressive strides in reducing” chronic absenteeism and that “offer valuable lessons on how schools can re-engage students.” Among them is a 24% drop in absenteeism at Dahlonegah Public Schools, which hired a school-based police officer to visit the homes of students who failed to attend school. The district also credited improvements to “a welcoming and engaging school environment.”

The state education department didn’t respond to requests for comment.

“Families have to be involved and they have to be partners and they have to take responsibility for getting kids to school, but it’s not solely about what families do or don’t do,” Chang said. “I think it’s a mistake to assume it’s only one group’s responsibility. This is a shared responsibility.”

‘Broken families, no economic opportunity, no education’

Johnson, the district attorney, said his office has stepped up to address a problem that state education leaders have failed to solve. He took particular aim at the state’s high-profile education secretary, Ryan Walters, who has become an outspoken champion of conservative education causes.

Yet, as far as chronic absenteeism goes, Johnson said the state schools chief “has no interest in talking about” the topic except “when he could get a soundbite on Fox News.” The state education department did not respond to Johnson’s comments.

The 51-year-old father of four also pinned persistent chronic absenteeism on parents — those living in poverty, in particular. Children in his district who most often miss school, he said, are “kind of feral.”

“My friends generally don’t have children that are in crisis because, just economically speaking, they’re on the higher end of the spectrum,” Johnson told The 74.

Johnson said there are about 7,500 K-12 children in the counties that make up his district and estimated that at least 30% contend with “economic poverty, multi-generational drug abuse, domestic abuse in the home, broken families, no economic opportunity, no education.”

“If you live in a school district where there is a real high poverty level and a real high incarceration rate, then a lot of times you’re going to get kids that have been raised in those environments,” Johnson said. “So you’re going to have a lot more challenges with that group than you would if every person had a four-wheel drive vehicle and a bass boat in their driveway and everybody has a good industrial job and is making a good living and providing for their families.”

Johnson said schools should play a role in encouraging students to go to school, but when that doesn’t work, threats of jail are needed. In Pontotoc County, just two truancy charges were filed against parents in 2023, according to data provided to The 74 by Johnson’s office. That number jumped to 20 last year and, so far this year, there have already been eight.

David Blatt, the director of research and strategic impact at the nonprofit Oklahoma Appleseed, questioned the accuracy of the data and said it could be an undercount. He said he attended a truancy court case in Ada last year where as many as 30 parents and students made appearances before a judge that lasted just 60 to 90 seconds each.

In a report last year, Blatt found that truancy laws were enforced inconsistently across the state and urged policymakers to adopt interventions and supports for families to address chronic absenteeism rather than criminalize them. Blatt backs the legislation to remove chronic absenteeism as a school accountability measure, acknowledging that certain attendance barriers are outside of educators’ direct control. But he said Johnson’s characterization of the problem is “rather harsh and one-sided.”

Rather than being apathetic toward their children’s education, he said many parents struggle with work responsibilities and transportation while children wrestle with in-school factors that can discourage attendance, such as persistent bullying.

“There may be cases where being called before a judge will help convince them of the seriousness of things, but for other cases, it’s just going to compound their problems,” Blatt said. “Adding court appearances and fees and fines doesn’t solve their problems. It just adds to them.”

Yet for Johnson, the issue stems from a lack of repercussions. By enforcing truancy cases, he said schools have “a little bit of a weapon” against parents whose children are missing school and can threaten them with jail time. Most of the time, he said, threats alone improve student attendance and in many cases the charges wind up getting dismissed.

In fewer than a dozen instances, he said, his truancy crackdown has led to parents serving time behind bars.

“Generally, they’ll go in for about four hours,” Johnson said. “We’ll give them the taste of it.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)